Ferragosto, the 15th of August, is one of Italy’s most important and most cherished holidays. It has its origins in antiquity, and has changed and evolved over the centuries, but as Gianni Di Gregorio’s wonderful film Pranzo di Ferragosto illustrated so powerfully, the Italian who finds him/herself working or away from family on this summer holiday feels especially hard done by.

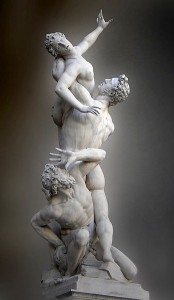

The Rape of the Sabine Women by Giambologna (Jean de Boulogne)

The roots of the holiday come from the agricultural calendar. The Roman festival of the Consuali, which occured in August (either on the 23rd, or on the 18th if you accept the version of Plutarch in his Life of Romulus) and again in December, had various significances but it was no accident that each festival was tied in to harvests and granted days of rest to workers and animals.

The Consuali, which was supposedly instituted by Romulus, the founder of Rome, is also tied up with the myth of the Rape of the Sabine Women. According to various retellings, it was at the first games for the Consuali that the Sabine Women were abducted, to become the future wives and mothers of Rome. If this version is to be accepted, then Ferragosto ties in with some of the most important foundation myths of the Roman Empire.

Jump forward to 18 B.C and the Emperor Augustus, responsible for the so-called pax-romana, and an extensive program of monument building and city works (see the impressive Arco di Augusto in Rimini, for example). To celebrate this period of growth, prosperity, and peace within the Empire, a new holiday was instituted, the feriae Augusti which ran for the whole month of August. Various Gods were celebrated during the month, including the Goddess Diana, patron of Wood, Cycles of the Moon and Motherhood (13th of August), Vertumno the God of the seasons and the harvest, Conso the God of the fields, and Opi the Goddess of fertility (whose feast Opiconsiva, was celebrated on the 25th of the month).

The feast was particular in that it was the sole occasion when all classes of Romans could celebrate together – master and servant, noble and slave alike. Even the beasts of burden were given a pause, and garlanded with flowers.

This aspect of the feast, perhaps, explains its continuing importance and place in the collective imagination of Italy. Ferragosto is a feast when everyone, from Billionaires like Silvio Berlusconi, through to the factory workers of the big industrial cities like Turin and Milan all get to take a break and head either to the Mountains, or more likely to the sea.

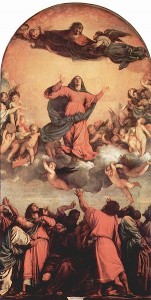

Nowadays the feast actually being celebrated by Italians on the 15th of August is nominally the feast of the assumption, a Roman Catholic feast day celebrating the belief that Mary, the mother of Jesus, at the end of her earthly life was assumed physically into heaven.

15th of August is the catholic feast day of the assumption

It’s interesting to note that the origins of this feast-day itself have been lost in time. It’s not even sure where or when the popular belief relating to the assumption began – though certainly in the 4th and 5th centuries it was appearing in texts, and it has been speculated that the feast was introduced by the Council of Ephesus, though this remains open to debate.

It was, in all probability, the Byzantine Emporor Maurice who first instituted the feast day on the 15th of August, in the 580’s in the Eastern Empire. It’s suggested, though, that Mary’s feast day in Italy prior to the seventh century was held in January.

What is clear, though, is that by the middle ages the feast day was solidly ingrained in Roman Catholicism, with Pope Leo IV adding an octave to the feast day in 847. Local churches throughout Europe have different traditions and festivities that add other feast days in August in honour of the Virgin Mary (for example, the feast of the glorification of Mary, celebrated by the Swedish Brigittines on the 30th of August).

The co-habitation between a pagan and christian festival, in terms of customs and celebrations can be seen on various different levels. For example, to celebrate the assumption, the Church apparently (there are lots of non-descript references to papal decrees ) made it obligatory during the renaissance to recognise workers with a bonus at this time – something that happened during the roman festivities where servants would recognise their masters and in turn recieve a bonus, a renewal of an important social contract. It has been suggested as well that this ancient and subsequently christianised tradition is the root of the modern day practice of the tredicesima or thirteenth month bonus workers receive at the end of the year.

The Kursaal bathing complex in Rimini in the 1800s

The Adriatic Riviera coast has become almost synonymous with Ferragosto in the popular imagination – the destination for thousands of Italian families, of all classes, who flee the cities to enjoy the beach and bathing. And if you’re talking about the Adriatic Coast, it’s hard not to talk about Rimini – the city where it’s estimated that at least half of the Italian population has holidayed at least once.

Ferragosto, though, hasn’t always been so closely associated with the beach – even in Rimini, as a browse through newspapers during August in the early 1800’s, before the creation of the bathing complex built in 1843 which revolutionised Rimini’s tourism, reveals. In 1806 there is a report of Cardinal Bellisomo, the bishop of Cesena, coming to Rimini to bathe in the sea – but he was a pioneer in the field. Throughout the 1820s and 1830s it was more popular, by far, to head to the hills of Covignano just outside Rimini for a ‘scampagnata‘ or picnic – so much so that in 1832 a local reporter spoke of a huge crowd, almost impossible to count, collected on the hills to enjoy foods like Piadina, Porchetta, and water melon.

Up until the start of the 20th Century Rome continued to celebrate the festival by setting up an impromptu lake in the capital’s Piazza Navona! The Piazza would be flooded, and people would either be sprayed with water or pushed into the piazza’s pool – linking the church festival with older rites which concentrated on Neptune and purification through water.

The ancient rites associated with the festival concentrated also on purification by fire, so it’s no surprise that in the countryside especially there are still bonfires lit in and around Ferragosto. In some places, like Trapani – in Sicily – there are processions where townspeople using torches burn grass alongside the procession.

There are also important cavalcades like the cavalcata dell’assunta in the Marche town of Fermo, where alongside the palio horse race there are historical re-enactments, flag throwing, and a step backwards through time.

While the official holiday is just one day, the 15th of August, it’s generally accepted still that the whole month of August is holiday season in Italy. On te first weekend of August the news bulletins are crammed with items about the ‘exodus’ as people leave the cities to head to the coast or the mountains. With the decline in industrial output and the closing of large factories this is a tradition that may well be dying out, but stroll the streets of Milan, Bologna, Turin or Rome during August and you’ll notice a marked difference.

The actual holiday has local variants throughout the country. In Siena the world-famous horse race, with its roots in the middle-ages (and back to Roman games where horse racing figured strongly), the Palio del’ Assunta takes place on the 16th in honour of the feast.

The thousands of people who take to the beaches of the Adriatic riviera, unbeknownst to themselves, re-enact some of the most basic ancient rites as they celebrate the spirits of fire and water. Starting a couple of days before, and running right up to the 15th there are loud, bright, and spectacular fireworks displays each night. Then, of course, there’s the bathing which, as we’ve seen, from the mid-1800s has become the classic way to celebrate Ferragosto – when you ask an Italian family what they’re doing for Ferragosto 99% will respond that they’re either going al mare (to the seaside), nelle montagne (to the mountains), or are resignedly remaining a casa (at home).

Ferragosto has been used by various film-makers and authors precisely because there is such a strong sense of what the festival is in Italy, so any deviation can create instant dramatic tension.

Gianni Di Gregorio's Pranzo di Ferragosto

Most recently, for example, Gianni Di Gregorio’s Pranzo di Ferragosto, a quiet and subdued film revolves entirely around expectations of what an ideal Ferragosto should be, and what the protagonists’ actual Ferragosto becomes. Di Gregorio stars in the film (which he directs) as an ageing bachelor who lives with his mother in Rome’s city centre. Behind in rent, he is effectively blackmailed into looking after his Landlord’s elderly mother over Ferragosto (while the landlord sets off for the holiday). His Mother’s doctor turns up shortly after also needing a similar favour (though he will spend the holiday working). With a house full of elderly women, he resigns himself to missing out on the festival – no sea or mountains for him. Not a lot happens, and yet it’s a beautiful and deeply moving film about ageing, society, death and relationships.

Dino Risi's 1962 film il sorpasso depends upon Ferragosto thematically

Dino Risi’s black and white classic il sorpasso (which was, apparently, a big influence on Denis Hopper when he wrote Easy Rider – its english language title was The Easy Life) opens with Vittorio Gasman wandering through Rome, deserted because it’s Ferragosto, looking for cigarettes. He is thrown together with a young student Jean-Louis Trintignant, and the two goad each other on into a quest that ultimately proves illusory.

Both films use Ferragosto as a prism through which to view Italian society – in Risi’s film it’s the Italy of the economic miracle, of the middle class, of playboys and an over-arching sense of entitlement. In Di Gregorio’s film it’s 21st Century Italy, with its ageing population and crumbling social services structure.

All this is a detailed and roundabout way of saying that Ferragosto was, is, and will continue to be one of Italy’s most imporant and dearly held festivals. It’s an inclusive one, from its roots, so wherever you are – be it in the mountains or at the seaside, soak up the atmosphere and don’t be shy in wishing people around you a Buon Ferragosto!

i wish to live in Italy

questo articolo mi fa venire ancora più voglia di estate, la notte di ferragosto falò sulla spiaggia e bagno di mezzanotte…